Introduction

For centuries, art was defined by galleries, museums, and wealthy patrons. Fine art—oil paintings, marble sculptures, and carefully curated exhibitions—was considered the highest form of human creativity. But in the late 20th century, a new kind of art exploded onto city walls, train cars, and abandoned buildings. Street art emerged as a rebellious, raw, and public expression of creativity. Once dismissed as vandalism, it now sits in some of the world’s most prestigious galleries, challenging the very boundaries of what counts as “real art.”

The relationship between street art and fine art has become one of the most fascinating cultural conversations of our time. Once seen as polar opposites—outsider vs. institution, illegal vs. sanctioned—they now blur together in ways that reshape both artistic practice and public perception.

The Roots of Street Art

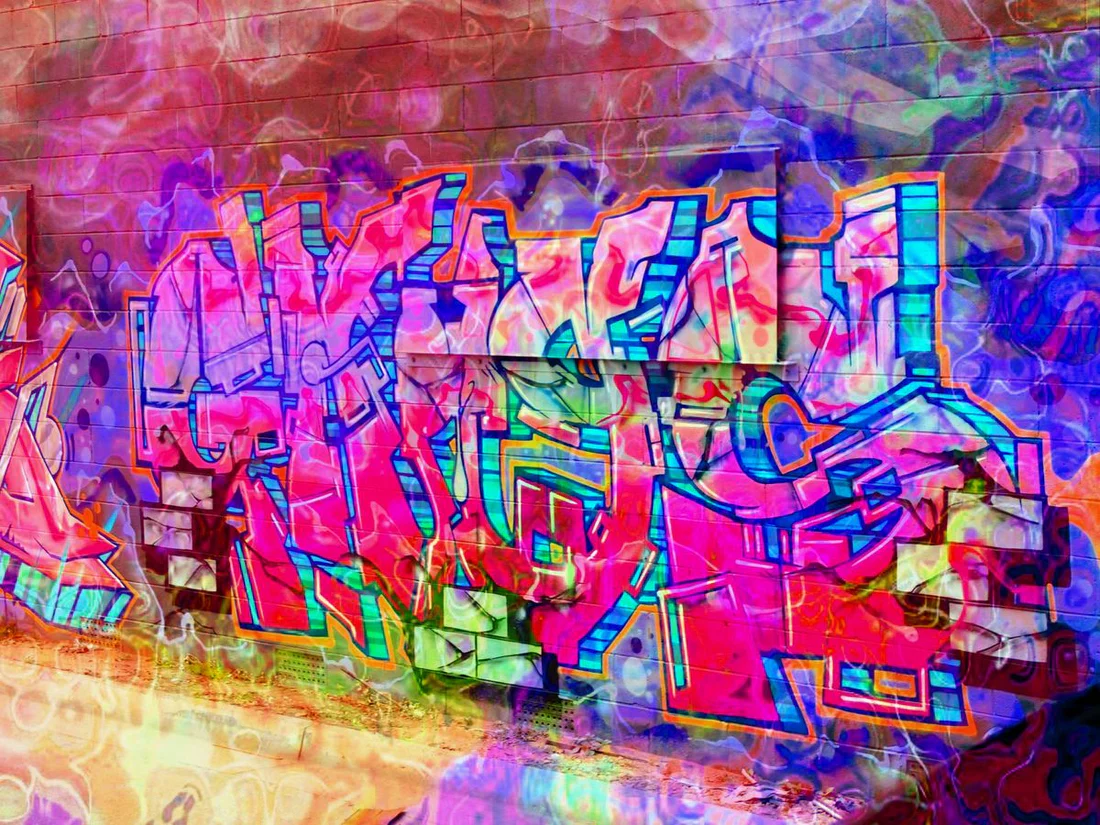

Street art is often associated with graffiti, which emerged in the 1960s and 70s in cities like New York and Philadelphia. Young artists, often from marginalized communities, used spray paint to tag their names on walls and subway trains. These tags evolved into elaborate designs, murals, and political statements.

Graffiti was more than decoration; it was identity, protest, and presence. For many, it was a way to claim visibility in societies that ignored them. Over time, street art grew beyond tagging to include stencils, wheatpaste posters, stickers, and large-scale murals. Artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring brought street aesthetics into galleries, paving the way for the artform’s legitimacy.

Fine Art: Tradition and Authority

Fine art, by contrast, has long been tied to tradition, authority, and exclusivity. From the Renaissance to modernism, fine art was created for elites—commissioned by kings, popes, and wealthy patrons, later curated by museums that determined what was worthy of preservation.

Fine art was not about accessibility but about prestige. It existed in controlled environments, where viewers were expected to appreciate it quietly and reverently. This exclusivity is precisely what street art challenged.

Clashing Worlds

When street art first gained visibility, it was seen as a threat to fine art. Museums dismissed it as vandalism, while city governments criminalized it. The tension between legality and creativity defined early street art’s rebellious image. Yet the energy and originality of the movement couldn’t be ignored. Critics began to see it as a legitimate form of artistic expression, albeit one that challenged the establishment.

The Blurring of Boundaries

Today, the lines between street art and fine art are increasingly blurred. Artists like Banksy, Shepard Fairey, and JR are celebrated in galleries while continuing to create provocative work in public spaces. Murals once considered criminal are now commissioned by cities to beautify neighborhoods.

Galleries, too, have embraced street art. Works once painted illegally on walls are cut out, preserved, and sold for millions. At the same time, street art has influenced fine art practices, with traditional artists incorporating graffiti styles, bold colors, and urban themes into their work.

Street Art as Political Voice

One of the most powerful aspects of street art is its accessibility. Unlike fine art confined to museums, street art lives in public spaces where anyone can see it. This makes it a potent tool for political and social commentary. From anti-war murals to feminist stencils, street art often speaks directly to communities and issues in ways fine art cannot.

Fine art has historically been political too, but often mediated through elites and institutions. Street art bypasses those gatekeepers, reaching audiences unfiltered and raw.

The Institutionalization of Rebellion

Ironically, as street art has gained acceptance, it has also been institutionalized. Murals are commissioned by corporations and governments, sometimes stripping them of their rebellious edge. Street artists who once painted illegally now sell canvases for high prices.

This raises questions: Can street art remain street art once it enters galleries? Does its meaning change when it is commodified? For some purists, the institutional embrace of street art dilutes its essence. For others, it represents recognition long overdue.

The Global Street Art Movement

Street art has grown into a global phenomenon. From São Paulo to Berlin, Melbourne to Cairo, urban landscapes are filled with murals that blend local culture with global aesthetics. Street art festivals attract thousands, and Instagram has given street artists global audiences. This globalization further blurs the line between fine art and street art, as international acclaim boosts their legitimacy.

Fine Art’s Response

Fine art has also evolved in response to street art. Many contemporary fine artists borrow urban aesthetics, incorporate graffiti-inspired techniques, or explore themes of public space and rebellion. The once-clear hierarchy between fine art and “low” art has collapsed, replaced by a spectrum where influences flow freely.

Conclusion

Street art and fine art may have started as rivals, but today they exist in dialogue. Street art has pushed fine art to loosen its elitist boundaries, while fine art has provided street artists with visibility and preservation. Together, they have reshaped the definition of art itself, making it more inclusive, diverse, and dynamic.

What once was vandalism is now celebrated. What once was elite is now challenged. The blurred boundary between street art and fine art reflects a broader truth: art is not defined by walls, institutions, or traditions, but by its ability to connect, provoke, and inspire.